As previously mentioned, general game playing programs can operate in a variety of different settings. They can co-exist with other players in a single standalone application; they can run in different applications that communicate with each other through direct message passing; and they can be implemented as separate applications that communicate with each other through a game manager.

What differentiates one setting from another is the nature of the executive program that manages communication between players and/or the game managre. There is a different executive programs for each of the various settings described above. For example, the standalone executive program manages matches between players running in a single application. The peertopeer executive program manages matches between players running in different applications and communicating with each other again without an intervening game manager. And the competition executive program manages matches between players running in different applications and communicating with each other through a game manager that coordinates game play.

In this chapter, we describe an executive program to manage players in a competition environment. We start with a discussion of how the executive calls the subroutines of a game player upon receipt of messages from a game manager, and we talk about how it returns results to the game manager. We then describe the basic capabilities the executive program provides for accessing states and game descriptions. Finally, we consider two search-free players in this environment, viz. legal players and random players. In Chapters 5 and 6, we look at complete search techniques (which are appropriate for small game trees); and in Chapters 7 and 8 we look at incomplete search techniques (which are necessary for very large game trees).

This conceptualization of games is an alternative to the traditional extensive normal form definition of games as game trees. In a game tree, each node is linked to successors by arcs corresponding to the actions legal in the corresponding game state. While different nodes in game tree sometimes correspond to different states, it is possible for different nodes to correspond to the same game state. (This happens when different sequences of actions lead to the same state.)

While extensive normal form is more appropriate for certain types of analysis, the state-based representation has advantages in General Game Playing. A state-based representation makes it possible to describe games more compactly; and, since game graphs are typically much smaller than game trees, it frequently decreases the computational cost of game analysis.

As computer programs, general game players can operate in a variety of different settings. They can co-exist with other players in a single standalone application. They can exist in separate peer-to-peer applications that communicate with each other using "state-sharing" technology. More commonly, they are implemented as separate applications in a managed competition setting..

By exploiting this structure, it is possible to encode games in a form that is more compact than direct representation. Game Description Language (GDL) supports this by relying on a conceptualization of game states as datasets and by relying on logic to define the notions of legality, rewards, and game termination in terms of these datasets.

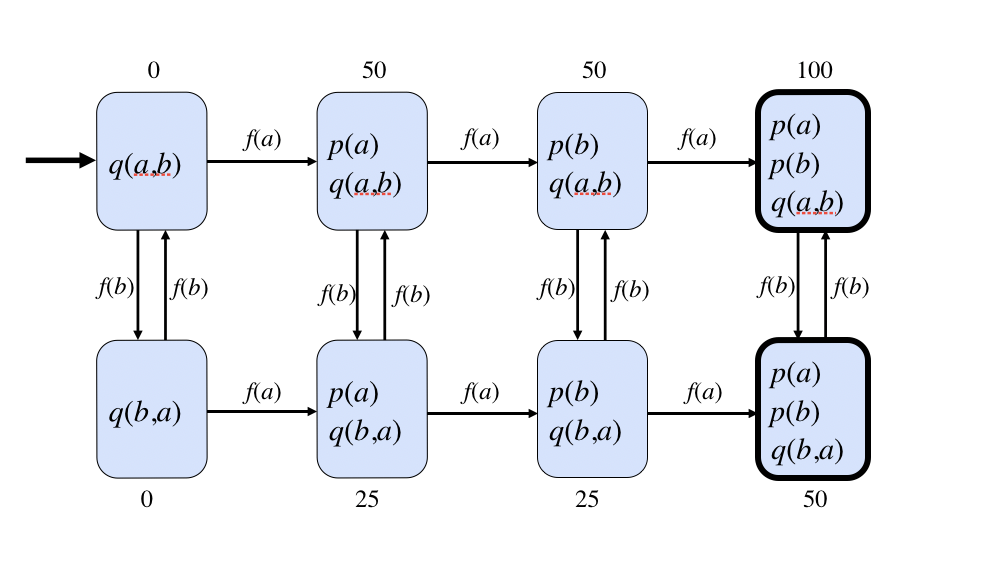

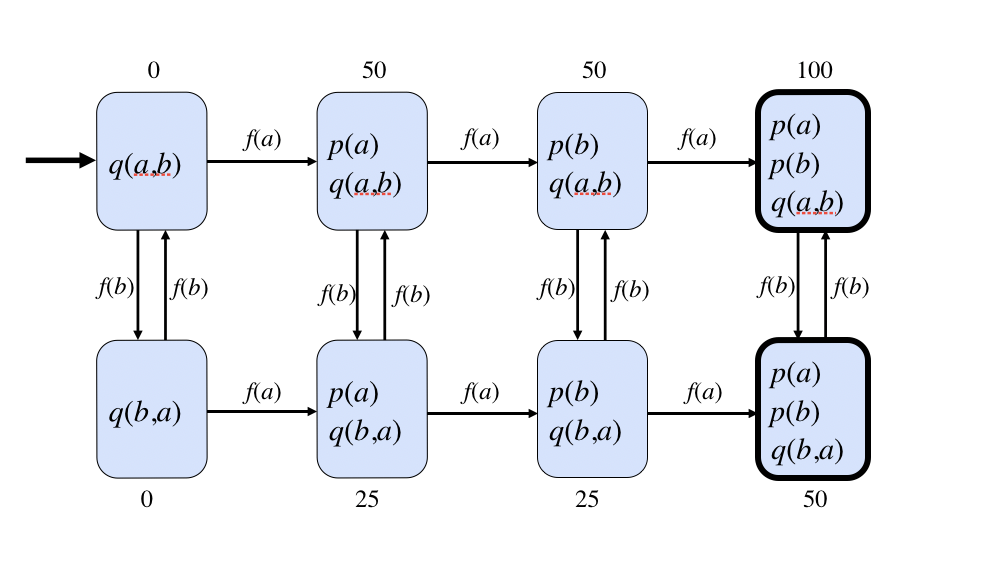

role(robot) base(p(a)) base(p(b)) base(q(a,b)) base(q(b,a)) action(f(a)) action(f(b)) init(q(a,b)) init(control(robot)) |

legal(f(a)) :- ~p(a) legal(f(a)) :- ~p(b) legal(f(b)) f(a) :: p(a) ==> ~p(a) & p(b) f(a) :: ~p(a) ==> p(a) f(b) :: q(X,Y) ==> ~q(X,Y) & q(Y,X) goal(robot,100) :- p(a) & p(b) & q(a,b) goal(robot,50) :- p(a) & ~p(b) goal(robot,50) :- p(b) & ~p(a) goal(robot,0) :- ~p(a) & ~p(b) terminal :- p(a) & p(b) & q(X,Y) |

Although GDL is designed for use in defining complete information games, it can be extended to partial information games. That said, the resulting descriptions are more verbose and more expensive to process.

Building a game player means writing defining the subroutines called by a GGP executive program. The subroutines called by all of the executive programs are listed below.